Yesterday, I discussed Shamir’s secret sharing and how it works. The TL;DR was a method to give \(n\) people a secret number so that any \(k\) of the recipients \((k\lt n)\) can reveal the secret. The method works by defining a \((k-1)\)-degree polynomial with the secret number as the constant term and then distributing \(n\) points on the polynomial. Once we have \(k\) points, we can recover the polynomial—and therefore the secret constant term—by interpolation.

We begin with a couple of constants and a function. The randp function uses strong-random from the ironclad library to generate cryptographically secure random integers between 0 and \(p-1\). We use it to generate the coefficients for the polynomial and the \(x\)-coordinates of the \(n\) points. The *prng* parameter holds the state for randp.

*P* is a 256 bit prime number. It’s the default size for the number of elements in our finite field. Because \(\mathbb{Z}_{p}\) is a finite field, you might think that we could simply try each element of the field to recover an encryption key based on the constant term of the polynomial. That would work for a low order field but using *P* gives us a field with \(2^{256}\) members rendering a brute force attack infeasible.

(defparameter *prng* (ironclad:make-prng :fortuna) "Holds the RNG state.")

(defparameter *P* 108838049659940303356103757286832107246140775791152305372594007835539736018383 "256 bit prime")

(defun randp (p)

"Generate a random number for the polynomial coefficents and sample points."

(ironclad:strong-random p *prng*))

Because we’re working in \(\mathbb{Z}_{p}\), “division” is a bit more complicated. The modinv function uses the Euclidean algorithm to compute the (mod \(m\)) inverse of a number. When we need to divide by some number, \(x\), we use modinv to compute its inverse and then multiply by that inverse to “divide.”

(defun modinv (a p)

"Find the inverse of a mod p, p a prime. Uses the Euclidian algorithm.

This is Algorithm X of Section 4.5.2 of TAOCP."

(labels ((euclid (u v)

(if (= (caddr v) 0)

(let ((u0 (car u)))

(if (minusp u0)

(+ u0 p)

u0))

(let ((q (floor (/ (caddr u) (caddr v)))))

(euclid v (mapcar (lambda (x y) (- x (* q y))) u v))))))

(euclid (list 1 0 a) (list 0 1 p))))

We’ll generate the \(n\) points by choosing \(n\) random, non-zero \(x\) values and evaluating the polynomial at those points. The efficient way to evaluate polynomials is with Horner’s methods. I wrote about Horner’s method previously.

(defun horner (a x)

"Evaluate the polynomial with coefficients in the array a at x."

(if (= (length a) 1)

(aref a 0)

(do* ((k (1- (length a)) (1- k))

(val (* (aref a k) x) (* (+ val (aref a k)) x)))

((<= k 1) (+ val (aref a 0))))))

The make-keys function uses randp to choose the polynomial’s coefficients (and thus the secret) and the \(x\)-values of the \(n\) points. Then it uses horner to generate the \(n\) points.

The xvals list is initialized to (0) so that 0 will not be chosen as an \(x\)-value. It’s discarded before xvals is input to the mapcar by the butlast.

(defun make-keys (n k &optional (p *P*))

"Returns a random secret and n distinct keys.

K keys are sufficient to recover the secret. Each key is a pair, a point

on a random polynomial over the field Z/p."

(let ((a (make-array k))

(xvals '(0))) ;ensure x=0 not chosen as a point

(dotimes (i k)

(setf (aref a i) (randp p)))

(while (< (length xvals) (1+ n))

(setq xvals (adjoin (randp p) xvals)))

(cons (aref a 0)

(mapcar (lambda (x) (list x (mod (horner a x) p))) (butlast xvals)))))

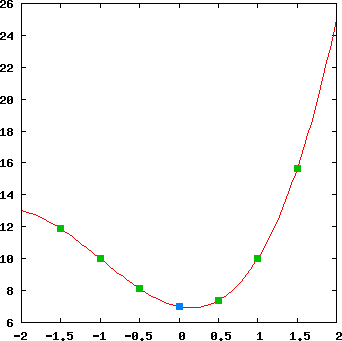

Given the \(k\) points \((x_{0}, y_{0}) \ldots (x_{k-1}, y_{k-1})\), we retrieve the secret by evaluating the polynomial resulting from the Lagrangian interpolation of the \(k\) points at 0. We can do this all at once by computing \[\sum_{i=0}^{k-1} y_{i} \prod_{\substack{0\leq{}j\leq{}k-1 \\ j\neq{}i}} \frac{-x_{j}}{x_{i}-x_{j}}\] as explained in yesterday’s post. Notice that retrieve-secret is an almost literal translation of the above.

(defun retrieve-secret (v &optional (p *P*))

"Recover the secret given k points and the prime."

(let ((k (length v))

(secret 0)

prod)

(dotimes (i k (mod secret p))

(setq prod (cadr (aref v i)))

(setq secret (+ secret

(dotimes (j k prod)

(unless (= j i)

(setq prod (* prod

(car (aref v j))

(modinv

(- (car (aref v j))

(car (aref v i)))

p))))))))))

As you can see, Shamir’s method is easy to understand and implement. None-the-less, it’s a powerful way of having a distributed secret.